If you’ve ever typed “Florida Man” into your Google

search bar, you know it’s true: real life is stranger than fiction - and often

funnier. So it should come as no surprise that nonfiction books can be equally

hilarious.

In the olden days (pre-Internet), information books

for children tended to be dry bones fact delivery systems. Today’s books are much

more than that. They offer context, connections, and narrative. And perhaps

most importantly, they engage and inspire young readers.

Humor is a high-octane tool for hooking a reader. And

a bit of rib-tickling makes the subject matter stick! That’s why I use humor frequently in my own

nonfiction writing, even for super-serious subjects.

Here’s how I keep kids cracking up from the Table of

Contents straight through to the glossary.

The Subject, naturally: When choosing

which experiments to highlight in my book Science on the Loose, I opted to

include “the famous fart experiment,” an actual study in which scientists in

the UK measured both the amount and intensity of flatulence in male and female

populations. While kids giggle and guffaw, they discover how to set up and

conduct a scientific experiment (starting with a hypothesis, controlling the

variables, accurate measurement, etc.) It’s real science, it’s really funny,

and it’s explosively (!) engaging.

Approach: Even when the subject matter is not inherently funny, like an authoritative biography of a forgotten math genius, a light touch can go a long way. As an example, consider the tone I used in Emmy Noether: The Most Important Mathematician You Never Heard Of: “Emmy was much smarter than everyone else in her classes. The other students knew it and didn’t much like it. After all, girls were not supposed to be smarter than boys (See page 6: not be geniuses.”)” The style is direct and wry. Lots of the side notes and captions are laugh-out-loud funny. The hits of humor highlight Emmy Noether’s own genial personality and acts as leaven for a text that might otherwise be dense with math and physics.

Language: Anyone who’s had to slog through an academic paper knows that convoluted sentence structure and jargon can make even a simple subject hard to understand and deadly dull. When I write for kids, I pay careful attention to my word choice, with a special focus on the way words and sentences sound. I use rhymes and alliteration liberally and tons of puns. I up my game with major league word play, and up the chuckles with sly juxtapositions (see what I did there?).

Some words are funnier than others. Words with the letter K in them, like kazoo or nincompoop, are widely considered the funniest. Repeated syllables also solicits smiles. In a choice between apples or bananas, I always go bananas.

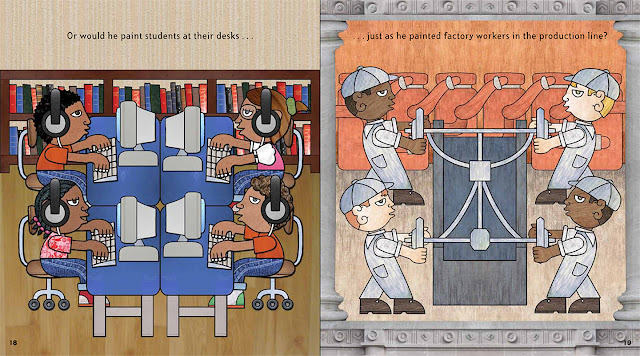

Art: The illustrations are an important part of many books for children. They set the mood and convey lots of information that round out the text. A weighty subject, like dinosaur taxonomy, can get a lift from lighthearted pictures.

This is very much the case in That’s No Dino! – Or Is It?, my

primary-level book about, yes, dinosaur taxonomy. Goofy, brightly-colored

graphics by Marie-Eve Tremblay definitely get the giggles going – and clarify

the subject matter in a way that is accessible to even young readers.

So if you’re no-nonsense about nonfiction, go for books that serve up giggle fits along with the facts. Because well-researched information is absolutely a laughing matter.

Give It a Try: Choose a nonfiction topic that appeals to you. How can you make it fresh and fun?

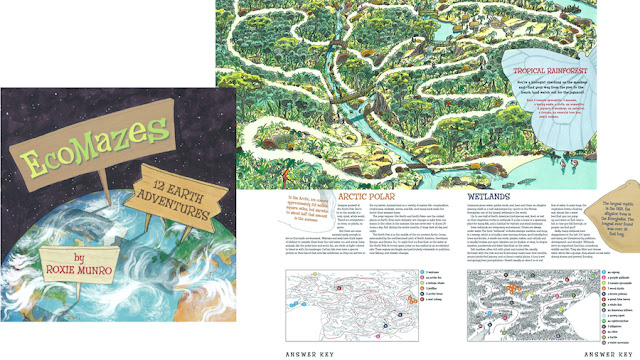

First, noodle around with your approach. If you’re writing about the rainforest,

for example, think about different, unexpected approaches that lend themselves

to humor. For example, you might present the Amazon from the point of view of a

sloth – upside down!

Once you’ve got your angle, write a sample introduction. Try a variety

of tones. Pick one that best captures the subject - and your own unique voice.

When you’ve got something that you think has potential, tweak your text

until it feels light and fun on your tongue.

Humorous writing can be hard to pull off, especially if you feel nervous

about putting yourself out there. Like all other writing skills, it requires

practice and courage. So, stick with it!

The verbal skills you develop will be useful in all your writing.

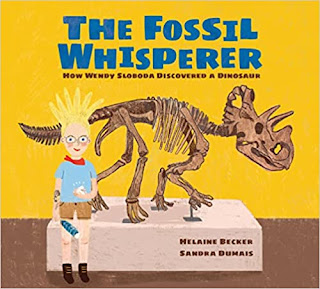

Meet the Author Helaine Becker is the award-winning author of more than 90 books for children and young adults, including the international bestseller Counting on Katherine: How Katherine Johnson Saved Apollo 13 and An Equal Shot: How the Law Title IX Changed America Forever. Recent nonfiction titles include Pirate Queen: A Story of Zheng Yi Sao and Emmy Noether: The Most Important Mathematician You Never Heard Of. Watch for The Fossil Whisperer: How Wendy Sloboda Discovered a Dinosaur later this spring.